如果你关注体育,便可能看见过运动员在场边,滚动着一个泡沫轴/按摩球,或是在理疗师的帮助下拉伸肌肉,同时借助筋膜枪的冲击进行放松。其实这些都属于筋膜松解术的各种形式,这种康复手段在美国已经普遍推广,并且成为了物理治疗师、手法治疗师、整骨医师、私人教练等必备的进阶课程,也融入了许多运动爱好者的日常生活。

那么筋膜松解术究竟是什么,它真的有实验依据、实际效用吗?

本文目录:

1. 筋膜的定义及其和健康的联系

2. 筋膜松解术和震动疗法的原理及作用

3. 筋膜松解术的实施和注意事项

一、什么是筋膜系统?

筋膜是包裹全身各部的结缔组织,它覆盖体壁,插入肌群,附着于骨,包绕血管,是一种缠绕、包围、保护和支撑人体结构的三维网状基质。筋膜是一个无中断的整体,从颅骨下延至足底,从内部伸展至外部,组成了人体本身的形态和形体。

由于筋膜分布于人体所有其他结构中,它被认为是人体中最庞大的系统(Pischinger,2007)。筋膜拥有比相应肌肉多10倍的感觉神经受体(van der Wal,2009)。筋膜系统是人体细胞生活的直接环境,这个张力网络会根据施加其上的局部张力要求而适应其纤维排列和密度(Schleip et al.,2012)。

筋膜本身具有不同程度的弹性,能够收缩和放松,因此能够响应负载、压缩和应力。它对组织有支持和约束作用,能改变肌力的牵引方向,以调节肌力的运行,具有姿势性功能和运动功能。很多酸痛症状和健康问题,都可以通过对相关筋膜的调理和治疗得到缓解。

人的一举一动都会牵扯到筋膜,它会因创伤而缩短、固化或增厚,从而为身体带来损伤、炎症和不良姿势,最终影响身体的生理适应能力。我们通常将其称为“筋膜粘连”,该网络任何部分发生的变形都会对整体结构产生负面影响。随着时间推移,筋膜受限处会不知不觉传播开来。运动缺乏灵活性和自发性会导致身体出现更多创伤、疼痛和受限,使人体在三维偏离垂直重力轴,致使运动和姿势出现生物力学低效和高耗能现象。

临床上,骨骼肌疼痛、关节功能受限、筋膜炎、肌劳损等常与肌筋膜疼痛综合征有关,或者是骨骼肌内有活化的疼痛触发点(激痛点MTrPs)。美国流行病学调查显示,75%的疼痛门诊患者都涉及到MTrPs,甚至85%慢性疼痛病人也与此关联。

根据组织器官综合研究专家Thomas W.Myers的理论,人体有7条主要的筋膜链:

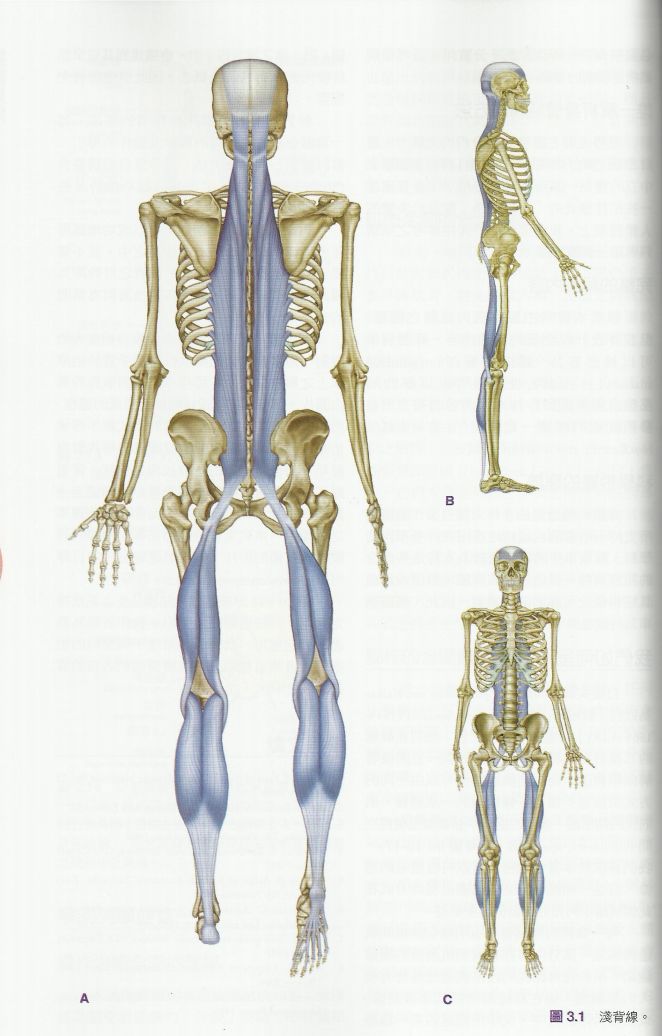

1.浅背线——起于脚底,向上延伸,绕过头顶,止于眉骨

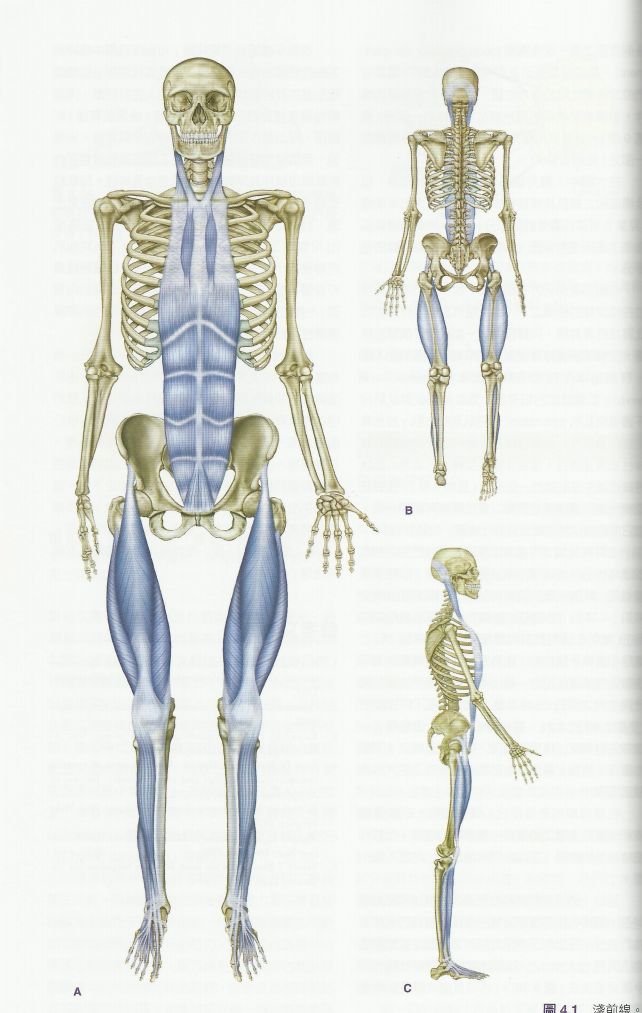

2. 浅前线——起于脚尖上部,止于耳后乳突

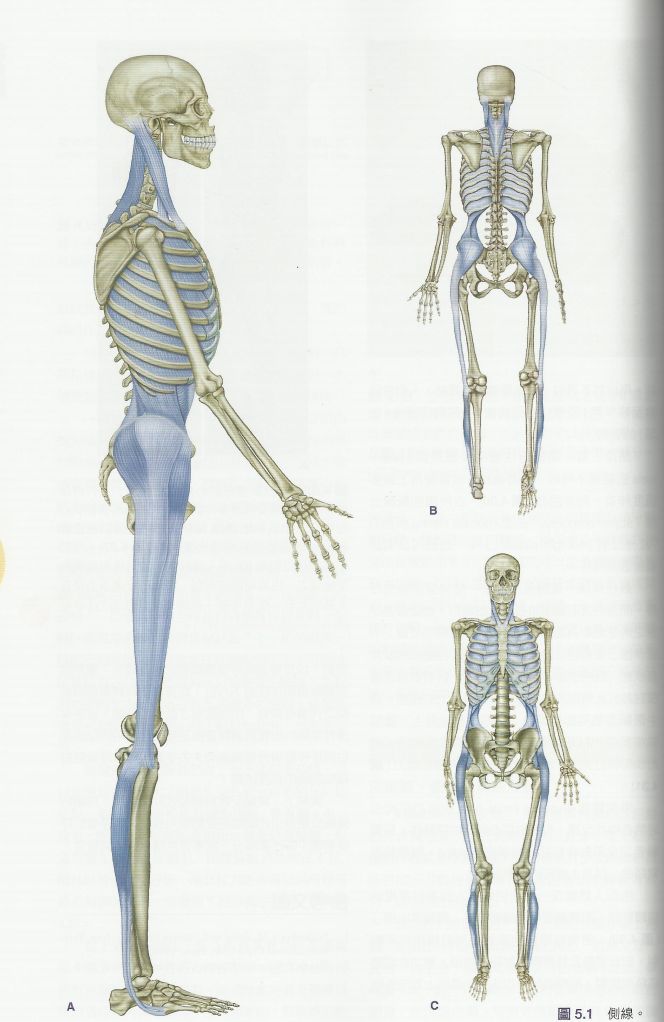

3. 侧线——沿着下肢、髋和腹外斜肌侧面延伸

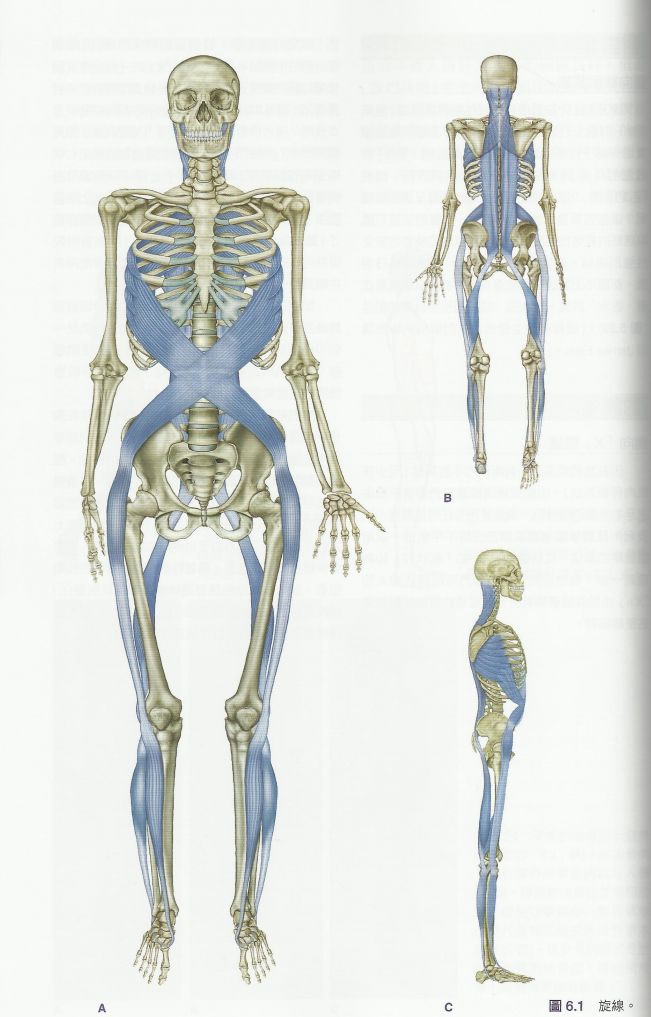

4.螺旋线——从一侧向另一侧,沿着身体环绕

5.深层前侧线——沿着脊柱和下颌,在深层延伸

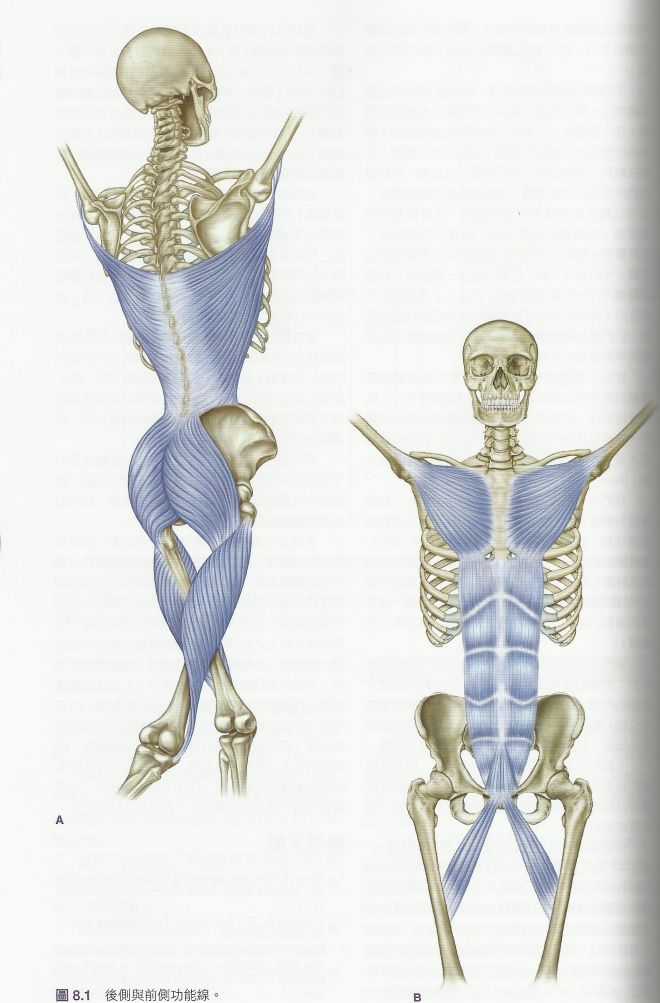

6. 功能线

7. 前臂线

筋膜链理论的特点及作用

- 对传统的肌肉解剖理念提出了挑战

在传统解剖理念中,每条肌肉都有特定的起止点。例如,胸大肌起于锁骨内侧半、胸骨体和1-6肋软骨以及腹直肌鞘前壁,而止于肱骨大结节。但实际上在解剖中却不是这样的——肌肉只有一部分起于或止于骨膜上,而还有一部分是以筋膜的形式与相邻的特定肌肉相连的。比如胸大肌和腹直肌就会以筋膜的形式在腹直肌鞘前壁处相连。

起止点的理论为肌肉位置和功能的学习提供了很多便利,但也同时限制了我们的思维:它使我们从分解的角度来讨论人体,而忽视了其整体的功能。人们简单地认为,只要将单块肌肉的功能简单叠加,就可以得出人类动作和稳定时所需要的复杂功能;但人体(骨骼肌肉系统)是一个张力均衡的结构——骨骼系统形成了结构外形,而行走在骨骼间的肌肉(肌筋膜链)则起到维持结构外形的作用,肌筋膜链的张力调整整个结构的平衡。

理想的人体可以使内部的总张力与相对应的总收缩力达到平衡,使人体的运作达到最有效的状态。当中的任何的一部分由于各种原因导致其张力发生变化,都会导致整条筋膜链上的另外某一部分(或整条链)发生张力的改变——筋膜网络好比一件毛衣,牵一发而动全身,时间久了,就会产生疼痛和人体体态结构的变化。

2. 很好地解释了人体代偿的规律

所谓代偿,就是某些器官因疾病受损后,机体调动未受损部分和有关的器官、组织或细胞来替代或补偿其代谢和功能,使体内建立新的平衡的过程。例如,当我们左脚扭伤,走路的时候右脚就会更多的来用力,来代替一部分左脚的功能。代偿只是身体为了妥协而耍的“小聪明”,它会让我们人体的某些部分使用过度,从而造成劳损、酸痛、筋膜炎等等症状。

筋膜链理论给了我们10类,共20条筋膜链,就像地图一样,医师从而可以循着它指引的路径来找到代偿的引发原因,从而从根本上解决疼痛、劳损等问题。

3.帮助提高人体柔韧度和关节活动范围

当我们进行拉伸时,很多情况下都没有到达肌肉真正的终点位置,因为肌梭会预先收紧一部分肌纤维,使其不能充分地伸展,所以只有较短的肌纤维是被拉伸的,还有一部分还处于松弛状态。那么,是什么造成这些肌梭紧张收缩的呢?有可能是过去的旧伤,可能是因久坐或卧床,长期维持了某种缩短的状态,也可能是环境过冷或潮湿(湿寒入体)。实验显示,一组肌群并不能独立于周边软组织于相关肌肉之外而被单独放松。运用筋膜链理论,可以很好地帮助我们充分拉伸,提高运动效率。

二、筋膜松解术的原理及作用

Kegerreis博士指出:筋膜松弛术(MFR)是利用筋膜系统,促进机械性、神经心理性与适应性潜能的操作观念与治疗哲学。MFR是一种软组织疗法,也是一种康复工具。治疗师通过感知各个平面上可能导致功能疼痛或障碍的紧张、受限和粘连区域,施加持续的压力或震动,以解决组织阻力障碍。这是一种以客户感受为主导的治疗,也可以通过设备(泡沫轴/按摩球)自行实施。

NASM医学会主席Mike博士阐释道,压力和震动可激发人体的机械性、神经生理性与适应性潜能,帮助身体自我修复。筋膜松解术的操作原理与治疗成效与筋膜内的各种机械受器(machanoreceptors)有关,主要包括高氏受器(Golgi receptor)、帕西尼受器(Pacini receptor)、类帕氏小体(Paciniform receptor)、鲁氏受器(Ruffini receptor)与间质受器。借由这些受器,筋膜将讯息传达至大脑(主要为自主神经系统)引发后续效应。Schleip(2003)提出自主神经回馈路径(下图)以解释肌筋膜松弛术如何经由受器,影响神经系统达到放松软组织的效果。

同时,结缔组织具有类似液态水晶的,受压力时传导电信息的趋势(压电现象)。结缔组织在受压力处理时倾向于变成液态,在未被处理时变得更加固态(触变现象)。对此按摩和锻炼能起到很好的作用,通过压力震动配合运动,有利于基质变得更加稀薄柔软,不易凝结。

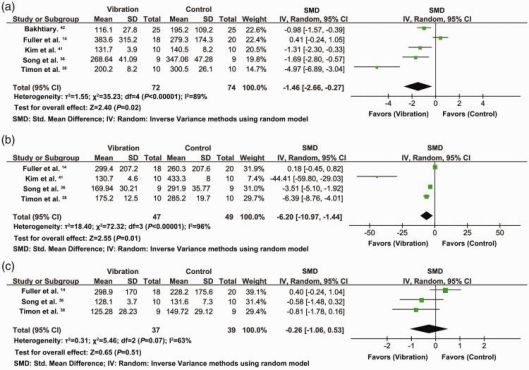

由于筋膜的物理特性,没有任何常规检查(如X射线、CAT扫描、脊髓成像、肌电图)能显示筋膜受限,因此筋膜科学依旧充满谜团。几十年来,美国国家医学院进行过许多实验,来探究震动按摩(LV,WBV)对DOMS(延迟性肌肉酸痛,即运动过后的肌肉僵痛)的影响,主要采用「视觉模拟评分法」(visual analogue scale,VAS)和「肌酸激酶」(Creatine Kinase,CK)作为指标。数据分析显示,震动疗法可以缓解DOMS,降低VAS和CK水平,是一种有效的理疗方法。

然而,碍于实验的规模和必然的误差,还需进一步的研究来提供更充分的证据。人体是个极为复杂的系统,震动疗法在缓解DOMS过程中的具体机制还有待医学解释。学界一些流行的假说是,震动疗法可刺激机械受器(machanoreceptors)来影响神经系统,以达到放松软组织的效果,或者通过压电、触变现象来影响组织粘滞性,所以能感受到组织软硬度(松弛感)的变化。总之,震动按摩有一定的康复效果,也正风靡当今美国运动界,不过筋膜学科仍不成熟,有许多机理还未得到阐释,筋膜松解术的长期影响也有待探明。

三、筋膜松解术的正确实施

使用筋膜球/震动轴进行放松时,通常需要体重将护理的区域压在按摩轴/球上,采取仰卧位、俯卧位、站姿靠墙等,来回滚动并定位压痛点(敏感酸痛区)。可加入动态拉伸,即在定点放松某块肌肉的同时,适当移动关节(屈曲、拉伸、内旋、外旋),以优化活动范围和灵活度。也可以抓握震动中的轴/球进行平板支撑,以提升肌肉的活性、平衡力。

注意事项:

1. 保证姿势正确,注意收紧腹部,维持核心发力。松垮的核心会导致肌肉代偿,对人体造成损伤。

2. 徐徐滚动,每个肌群1-2按摩分钟左右,可以在激痛点停留30秒

3. 保证震动轴/球处于软组织部位下,避开骨头和关节

4. 动作的过程中保持正常呼吸,不要憋气

5. 在热身或运动后再做震动轴练习

使用筋膜枪进行放松时,先触诊寻找粘连处与激痛点,根据肌纤维的走向,依次顺着、横跨肌纤维滑动筋膜枪。可先装载接触面积大的理疗头,采用高档位(大频率)来刺激表层软组织,仅使用筋膜枪自身的重力即可;其后可调成低档位(小频率),换成接触面较小的枪头,适当施加压力以深入刺激深层组织。当然,也可以进行动态疗程,即在定点按摩的同时活动相应肌肉(屈曲、拉伸、内旋、外旋),以取得深层的放松效果。

注意事项:

1. 作用于肌肉(软组织),注意避开附近的骨头和关节

2. 压力适当,注意枪体的回弹与稳定,以免造成不必要的损伤

3. 尽量隔着衣物/毛巾进行按摩,以免磨损皮肤,引发敏感反应

4. 疗程时间不宜过长,以免产生不良反应,适得其反

5. 气垫头和橡胶头材质较软,适合对振动敏感的新用户及长辈;小平头适用于大块肌肉,如大腿腘绳肌、小腿肚腓肠肌、臀大肌;叉形头可用于很多敏感处,比如跟腱处、脊椎两侧;子弹头适合筋膜粘连受限处,提供深层的震动疗法。

参考文献:

1. Meamarbashi A. Herbs and natural supplements in the prevention and treatment of delayed-onset muscle soreness. Avicenna J Phytomed 2017; 7: 16–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Koh HW, Cho SH, Kim CY, et al. Effects of vibratory stimulations on maximal voluntary isometric contraction from delayed onset muscle soreness. J Phys Ther Sci 2013; 25: 1093–1095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Gulick DT, Kimura IF. Delayed onset muscle soreness: what is it and how do we treat it? J Sport Rehabil 1996; 5: 234–243. [Google Scholar]

4. Yu JY, Jeong JG, Lee BH. Evaluation of muscle damage using ultrasound imaging. J Phys Ther Sci 2015; 27: 531–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Wheeler AA, Jacobson BH. Effect of whole-body vibration on delayed onset muscular soreness, flexibility, and power. J Strength Cond Res 2013; 27: 2527–2532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Dupuy O, Douzi W, Theurot D, et al. An evidence-based approach for choosing post-exercise recovery techniques to reduce markers of muscle damage, soreness, fatigue, and inflammation: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Physiol 2018; 9: 403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Cheung K, Hume P, Maxwell L. Delayed onset muscle soreness: treatment strategies and performance factors. Sports Med 2003; 33: 145–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Cochrane DJ. Effectiveness of using wearable vibration therapy to alleviate muscle soreness. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017; 117: 501–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Rittweger J, Mutschelknauss M, Felsenberg D. Acute changes in neuromuscular excitability after exhaustive whole body vibration exercise as compared to exhaustion by squatting exercise. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2003; 23: 81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Sands WA, McNeal JR, Stone MH, et al. Flexibility enhancement with vibration: acute and long-term. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006; 38: 720–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Verschueren SMP, Roelants M, Delecluse C, et al. Effect of 6-month whole body vibration training on hip density, muscle strength, and postural control in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19: 352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Costantino C, Gimigliano R, Olvirri S, et al. Whole body vibration in sport: a critical review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2014; 54: 757–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Lee CL, Chu IH, Lyu BJ, et al. Comparison of vibration rolling, nonvibration rolling, and static stretching as a warm-up exercise on flexibility, joint proprioception, muscle strength, and balance in young adults. J Sports Sci 2018; 36: 2575–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Fuller JT, Thomson RL, Howe PRC, et al. Vibration therapy is no more effective than the standard practice of massage and stretching for promoting recovery from muscle damage after eccentric exercise. Clin J Sport Med 2015; 25: 332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Dabbs NC, Black CD, Garner J. Whole-body vibration while squatting and delayed-onset muscle soreness in women. J Athl Train 2015; 50: 1233–1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Mohammadi H, Sahebazamani M. Influence of vibration on some of functional markers of delayed onset muscle soreness. Int J Appl Exerc Physiol 2012; 1 http://www.ijaep.com/index.php/IJAE/article/view/59 [Google Scholar]

17. Broadbent S, Rousseau JJ, Thorp RM, et al. Vibration therapy reduces plasma IL6 and muscle soreness after downhill running. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: 888–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Kosar AC, Candow DG, Putland JT. Potential beneficial effects of whole-body vibration for muscle recovery after exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2012; 26: 2907–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Veqar Z, Imtiyaz S. Vibration therapy in management of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: LE01–LE04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Weerakkody NS, Percival P, Hickey MW, et al. Effects of local pressure and vibration on muscle pain from eccentric exercise and hypertonic saline. Pain 2003; 105: 425–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Lau WY, Nosaka K. Effect of vibration treatment on symptoms associated with eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 90: 648–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Custer L, Peer KS, Miller L. The effects of local vibration on balance, power, and self-reported pain after exercise. J Sport Rehabil 2017; 26: 193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Barnes MJ, Perry BG, Mündel T, et al. The effects of vibration therapy on muscle force loss following eccentrically induced muscle damage. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012; 112: 1189–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Manimmanakorn N, Ross JJ, Manimmanakorn A, et al. Effect of whole-body vibration therapy on performance recovery. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015; 10: 388–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Hazell TJ, Olver TD, Hamilton CD, et al. Addition of synchronous whole-body vibration to body mass resistive exercise causes little or no effects on muscle damage and inflammation. J Strength Cond Res 2014; 28: 53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Ayles S, Graven-Nielsen T, Gibson W. Vibration-induced afferent activity augments delayed onset muscle allodynia. J Pain 2011; 12: 884–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Gojanovic B, Feihl F, Liaudet L, et al. Whole body vibration training elevates creatine kinase levels in sedentary subjects. Swiss Med Wkly 2011; 141: w13222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Imtiyaz S, Veqar Z, Shareef MY. To compare the effect of vibration therapy and massage in prevention of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8: 133–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. De Hoyo M, Carrasco L, Da Silva-Grigoletto ME, et al. Impact of an acute bout of vibration on muscle contractile properties, creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase response. Eur J Sport Sci 2013; 13: 666–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Marin PJ, Zarzuela R, Zarzosa F, et al. Whole-body vibration as a method of recovery for soccer players. Eur J Sport Sci 2012; 12: 2–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Cormie P, Deane RS, Triplett NT, et al. Acute effects of whole-body vibration on muscle activity, strength, and power. J Strength Cond Res 2006; 20: 257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Dabbs NC, Black CD, Garner JC. Effects of whole body vibration on muscle contractile properties in exercise induced muscle damaged females. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2016; 30: 119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Orr R, O’Keefe K, Selvadurai H, et al. The effect of whole body vibration exposure on muscle function in cystic fibrosis patients-A pilot efficacy trial. J Sci Med Sport 2010; 13: e102–e103. [Google Scholar]

34. Pournot H, Tindel J, Testa R, et al. The acute effect of local vibration as a recovery modality from exercise-induced increased muscle stiffness. J Sports Sci Med 2016; 15: 142–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Abd T. The effects of vibration on delayed onset of muscle soreness before eccentric exercise in non-dominant biceps muscle. Physiotherapy 2015; 101: e28. [Google Scholar]

36. Song FM, Liu BX. Effect of whole body vibration intervention and static stretching on delayed onset muscle soreness after eccentric exercise (In Chinese). Journal of Shandong Sport University 2017; 33: 74–79. [Google Scholar]

37. Shen YH. Comparison of the effects of vibration training and static traction on the relief of delayed onset muscle soreness (In Chinese). Journal of Military Physical Education and Sports 2017; 36: 48–51. [Google Scholar]

38. Timon R, Tejero J, Brazo-Sayavera J, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration after eccentric exercise on muscle soreness and muscle strength recovery. J Phys Ther Sci 2016; 28: 1781–1785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Rhea MR, Bunker D, Marin PJ, et al. Effect of iTonic whole-body vibration on delayed-onset muscle soreness among untrained individuals. J Strength Cond Res 2009; 23: 1677–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Kim YS, Park HS, Song EM, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration on DOMS and comparable study with ultrasound therapy. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/92d0/5b93cc5aa12ee0bb7cb24924dc19c27e29b6.pdf (2011, accessed date month year)

41. Kim JY, Kang DH, Lee JH, et al. The effects of pre-exercise vibration stimulation on the exercise-induced muscle damage. J Phys Ther Sci 2017; 29: 119–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Bakhtiary AH, Safavi-Farokhi Z, Aminian-Far A. Influence of vibration on delayed onset of muscle soreness following eccentric exercise. Br J Sports Med 2007; 41: 145–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Aminian-Far A, Hadian MR, Olyaei G, et al. Whole-body vibration and the prevention and treatment of delayed-onset muscle soreness. J Athl Train 2011; 46: 43–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Guo J, Li L, Gong Y, et al. Massage alleviates delayed onset muscle soreness after strenuous exercise: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol 2017; 8: 747. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Asmussen E. Observations on experimental muscular soreness. Acta Rheumatol Scand 1956; 2: 109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Nakayama A, Aoi W, Takami M, et al. Effect of downhill walking on next-day muscle damage and glucose metabolism in healthy young subjects. J Physiol Sci Epub ahead of print 20 April 2018. doi: 10.1007/s12576-018-0614-8. [PubMed]

47. Ely MR, Romero SA, Sieck DC, et al. A single dose of histamine-receptor antagonists prior to downhill running alters markers of muscle damage and delayed onset muscle soreness. J Appl Physiol 2016; 122: 631–641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Hooren BV, Bosch F. Is there really an eccentric action of the hamstrings during the swing phase of high-speed running? Part II: implications for exercise. J Sport Sci 2016; 35: 2313–2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Fleckenstein J, Niederer D, Auerbach K, et al. No effect of acupuncture in the relief of delayed-onset muscle soreness: results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Sport Med 2016; 26: 471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Schultz L, Feitis R. The endless web. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books; 1996:vii.

51. Margulis L, Sagan D. What is life? New York: Simon and Schuster; 1995:90-117.

52. Varela F, Frenk S. The organ of form. Journal of Social Biological Structure 1987; 10:73-83.

53. McLuhan M, Gordon T. Understanding media. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press; 2005.

54. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:75.

55. Becker RO, Selden G. The body electric. New York: Quill; 1985.

56. Sheldrake R. The presence of the past. London: Collins; 1988.

57. Kunzig R. Climbing through the brain. Discover Magazine 1998; August:61-69.

58. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:80.

59. Oschman J. Energy medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:48.

60. Varela F, Frenk S. The organ of form. Journal of Social Biological Structure 1987; 10:73-83.

61. Snyder G. Fasciae: applied anatomy and physiology. Kirksville, MO: Kirksville College of Osteopathy; 1975.

62. Ho M. The rainbow and the worm. 2nd edn. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing; 1998.

63. Becker RO, Selden G. The body electric. New York: Quill; 1985.

64. Oschman J. Energy medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:45^16.

65. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:475-477.

66. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:448-452.

67. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:415.

68. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:472-473.

69. Hively W. Bruckner’s anatomy. Discover Magazine 1998; (11):111-114.

70. Schoenau E. From mechanostat theory to development of the ‘functional muscle-bone-unit’. Journal of Musculoskeletal and Neuronal Interactions 2005; 5(3):232-238.

71. Bassett CAL, Mitchell SM, Norton L et al. Repair of nonunions by pulsing electromagnetic fields. Acta Orthopedica Belgica 1978; 44:706-724.

72. Becker RO, Selden G. The body electric. New York: Quill; 1985.

73. Williams P, Goldsmith G. Changes in sarcomere length and physiologic properties in immobilized muscle. Journal of Anatomy 1978; 127:459.

74. Rolf I. The body is a plastic medium. Boulder, CO: Rolf Institute; 1959.

75. Currier D, Nelson R, eds. Dynamics of human biologic tissues. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1992.

76. Bobbert M, Huijing P, van Ingen Schenau G. A model of the human triceps surae muscle-tendon complex applied to jumping. Journal of Biomechanics 1986; 19:887-898.

77. Muramatsu T, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T. Mechanical properties of tendon and aponeurosis of human gastrocnemius muscle in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology 2001; 90:1671-1678.

78a. Fukunaga T, Kawakami Y, Kubo K et al. Muscle and tendon interaction during human movements. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 2002; 30:106-110.

78b. Alexander RM. Tendon elasticity and muscle function. School of Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds; 2002.

79. Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:413.

80. Janda V. Muscles and cervicogenic pain syndromes. In: Grand R, ed. Physical therapy of the cervical and thoracic spine. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988.

81. Varela F, Frenk S. The organ of form. Journal of Social Biological Structure 1987; 10:73-83.

82. Myers T. Kinesthetic dystonia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 1998; 2(2):101-114.

83. Myers T. Kinesthetic dystonia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 1998; 2(4):231-247.

84. Myers T. Kinesthetic dystonia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 1999; 3(l):36-43.

85. Myers T. Kinesthetic dystonia. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 1999; 3(2):107-116.

86. Gershon M. The second brain. New York: Harper Collins; 1998.

87. Oschman J. Energy medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

留言